Microplastics: small things creating big challenges for human health and the environment

Global testing leader ALS spoke with plastic pollution expert Dr. Sherri "Sam" Mason about the worldwide effort to understand and address the dangers of microplastics

Introduction

It’s nearly impossible to spend a day anywhere on Earth without using or encountering synthetic plastics, but they have only existed since a little over 100 years. The first fully synthetic polymer was introduced in 1907, and now plastics are everywhere: in our food and drink containers, clothing, bedding, toothbrushes, cosmetics, keyboards and vehicles – plastic is embedded in our lives, and its waste pollutes our land, water, air and bodies.

As a global testing leader, we are committed to raising awareness of the challenges posed by the manufacturing and use of plastics, particularly the potential dangers of the tiny plastic particles known as microplastics. Our clients need to know about the latest findings from research as well as the evolving regulatory landscape.

As part of that effort, we recently connected with subject matter expert Dr. Sherri Mason. A leading scientific voice on plastic pollution, Dr. Mason talked to us about what we know so far about microplastics, aspects of the problem researchers are looking at, and the importance of environmental monitoring in helping us determine the best approaches to minimizing the dangers of microplastics to the health of humans and our world.

Biography

Dr. Sherri A. Mason (aka Sam) earned her bachelor’s degree from the University of Texas at Austin. She completed her doctorate in Chemistry at the University of Montana as a NASA Earth System Science scholar. While a Professor of Chemistry at SUNY Fredonia, her research group was among the first to study the prevalence and impact of plastic pollution within freshwater ecosystems.

Sam has been featured in articles in the BBC, The Guardian, the New York Times, National Public Radio, and the Washington Post, among hundreds of others. Her work formed the basis for the Microbeads-Free Water Act, which was signed into US law in 2015. She received the EPA Environmental Champion award in 2016, Excellence in Environmental Research by the Earth Month Network in 2017, the Heinz Award in Public Policy in 2018 and the Great Lakes Leadership Award from the Great Lakes Protection Fund in 2021.

ALS: Thank you for speaking with us, Sam. First, can you tell us if there is a clear definition of what Microplastics are? Because we’ve heard people ask, “How can we do anything about it if we don’t know exactly what it is?”

Dr. Mason: I was at a conference a couple weeks ago where somebody said that there's not a clear definition, and I said, “Yes, there is.”

I was part of a United Nations working group and many of the scientists in the room wanted to define microplastics according to the definition of ‘micro’ – 1 millimeter and smaller – but there is already an international understanding of the definition. The consensus definition of a microplastic is any piece of plastic that is smaller than 5 millimeters but larger than one micron.

| Nanoplastic | 1-1000 nm |

| Microplastic | 1 µm-5 mm |

| Mesoplastic | 5-20 mm |

| Macroplastic | >20 mm |

Once we get below 1 micron, we're in the nanoplastic range. There is some debate on what is the lower boundary of what can be considered a nanoplastic, but I think we are coming to a consensus around 100 nanometers because once you get smaller than that, you're really talking about the molecular range. But that's still a little ambiguous at this point.

ALS: A recent article in Nature brought up that lack of clarity some people have about the definition and how they may use that to say, “We don't even know what they are, so don't ask us to do anything about it.”

That’s why it’s important to say, “No, we know what it is.” Then, for labs like ours, it helps us decide on the instruments we use to measure them.

Turning to the potential harm from microplastics, there are two aspects to this: chemical toxicity versus mechanical danger. Which do you see as the bigger danger or are they equal?

Dr. Mason: I don't think they're equal. And even on the chemistry side, we have to divide that into the polymer itself and then the chemical additives.

Maybe this is because I am also a chemist, but I do think the chemical side is the more concerning. The mechanical is more concerning when you're talking about macroplastics, and issues like organisms getting trapped in fishing nets and things like that.

But when you're in the microplastics range, even the fact that plastic can fill up a stomach and keep an organism from eating real food – a condition called food dilution – the mechanical aspects are ultimately less concerning than the chemical aspects of microplastics, especially the smaller microplastics.

We currently have more of an understanding of the chemicals than we do of the polymers.

ALS: Do we know how long microplastics stay in the body?

Dr. Mason: That's a good question, one we still haven't fully answered.

We have enough data at this point indicating that fibrous plastics tend to stay in the body longer. They have a similar structure to cell walls, so they may more easily infiltrate cells.

And when you're getting into the smallest microplastics – especially when you get into the nanoplastic range, where you’re talking about a miniscule fragment – those may quite easily move across your gastrointestinal tract, lung tissues, and so forth.

ALS: Follow up question: Given the complexity of microplastics, i.e. the ‘cocktail effect’, is there a concern that as long as we don't fully understand their diverse effects, people will use it as an excuse to say that you can't even prove they’re dangerous?

Dr. Mason: Yes, an industry trend is to be the ‘merchants of doubt’. That’s why trying to understand the human health implications of micro- and nanoplastics is at the forefront of research. One limit has been the challenge of monitoring the smaller microplastics, especially nanoplastics, that make their way across and infiltrate the body.

We haven't had a good way of measuring nanoplastics until researchers at Columbia University developed an instrument that was discussed in an article from January of this year. They're able to not just detect that you have a nanoparticle, but that it's plastic and what type of plastic it is, so that's critical to moving that understanding forward.

It also gets more complicated when you're talking about synergistic effects like, “I chewed on plastic toys when I was two. How is that affecting me now that I'm 50?”

There's always going to be this area where people can cast doubt.

It gets complicated.

ALS: It boils down to how to communicate, doesn't it? We don't want to be scaremongers, but there is evidence strongly suggesting microplastics are harmful to humans.

It may depend on many variables, and there are so many potential dangers now that we are looking for. For example, governments are spending billions of dollars to investigate the dangers of per and poly-fluoroalkyl substances (PFAS).

Regarding funding, where do you think microplastics research is versus PFAS and other substances?

Dr. Mason: That's a hard one, and part of it is because plastics are so complicated. It's not one thing. Dioxins and PFAS are hundreds of compounds.

With plastics, you have the polymer and the chemicals that are on it – and you have 10,000 different chemicals. And then there is the fact that they pick up things in the environment, so they become vectors, making it complicated.

The fact that the United Nations ranks microplastics second only to climate change in potential impact on the survival of our species says a lot. That's how they rank it, and that's why they're working on a Plastics Treaty.

There are so many pieces that can lead to problems, and the data we're getting is concerning. For example, we're starting to see connections to neurological disorders like Alzheimer's and Parkinson's.

Again, not trying to be scary, but the data is showing some connections there, and similarly, we already know that around 3,000 of the 10,000 chemicals that are used in the manufacturing of plastics have human health concerns. So, we have enough data to warrant being precautionary and changing our approach.

ALS: Some articles talk about how microplastics are not evenly distributed around the globe, and that although they’re found everywhere, there are hot spots. How do you see the danger to the general population, particularly those who may not be in a hotspot?

Dr. Mason: Yes, there are places where it's more prominent than others, but there's no place that is immune.

ALS: Some plastics manufacturers may say that they can’t be blamed for the health repercussions of microplastics.

Dr. Mason: When it gets into the environment it's an issue, but it's also an issue at the beginning of its life. It ultimately comes from fossil fuels.

I live in Pennsylvania, where hydrofracking is huge. Many people think of hydrofracking as being connected to energy. But half of what is produced from hydrofracking is going into plastics.

So, plastic is concerning from the beginning of its life, not just at the end of its life.

And it's having an impact on human health because of air pollution emissions as well as the little microplastic pellets that get released.

ALS: A big question then is: how do we reduce our reliance on plastic? Because it seems to many people that we can never overcome it. It’s not just plastic bags and straws. We're also talking about clothing. For example, people love buying a new fleece jacket that’s warm and cozy, but most fleece is made from synthetics that can shed.

How do we then convince people that plastic is not such a good idea?

Dr. Mason: One point is that we start with the biggest piece of the pie, which is a lot of the stupid plastic – packaging, straws and takeout containers – but yes, it is shocking how much clothing over the last 25 years is now made from synthetic materials. At least some companies are working on product materials that don't shed as much, and that's encouraging.

And there are others working on developing different materials. At a conference I attended a couple weeks ago, there were people looking into making materials out of algae and mushrooms – moving away from the synthetics and into more natural fibers. It's going to take time. It's not like we're going to switch off the plastics tap tomorrow, right?

It took 70 years for us to get to this point. It's probably going to take us 70 years to get away from where we're at, and technology is part of that.

It’s starting with the low-hanging fruit, and then working towards things that are more complicated.

ALS: Sometimes we determine something is harmful to humans, and then we find a substitute, but the substitute might be equally harmful. Is there a risk that we just kick the can down the road, like we've done in other areas?

Dr. Mason: Yes, absolutely. Part of that is that a lot of natural materials still use the same chemicals. For example, if you're mixing hemp with flame retardants.

I get emails from people who want to start a business, asking, “What do you think about this?”

And I often say, “Be aware of the fact that if you're mixing in toxic chemicals, it doesn't matter that you started with the natural material.”

I guess the hope is that we're gaining knowledge and experience. For example, things that are promoted as ‘BPA free’ may have replaced the BPA with BPS, which is even worse for humans – but unless you're in our field, you may not know this. When you talk about it, people's minds explode.

Our hope is that there gets to be enough of us pushing and trying to learn from experience that we don't repeat that history. It is a danger for sure. We're not out of out of the woods, and more people need to be talking about that. More thinking needs to happen, and I may be able to help with that.

ALS: Someone might say, “I know macroplastics are a problem: animals choking on straws or the plastic containers that hold soft drink cans together – but you're talking about these tiny little things, so how can that hurt me?”

Can you elaborate on the concerns and potential dangers around microplastics?

Dr. Mason: We do have some evidence that it affects fish. Fish that have ingested plastic don't swim as quickly, they get deformed. Their fight-or-flight instinct gets changed. Their ability to procreate changes, as does their ability to breathe. Oxidative stress becomes a real factor. So their survival rate is definitely impacted by microplastics.

In terms of human health, there's a great book called ‘Countdown’ by Doctor Shanna Swan, who's an ecotoxicologist, and Chapter 7 of that book is specifically on plastics. Dr. Swan shows that among other physical changes, sperm counts are going down and the ability of both males and females to procreate is decreasing. We’re hearing more about women having a hard time getting pregnant and having more miscarriages. We are having a harder time as a species getting pregnant, and it's because of the chemicals.

We have a strong body of evidence that chemicals are affecting the survival of our species, and plastics are one of the mechanisms that move those chemicals into people. We don't know whether that’s the primary means to move chemicals. Is it coming mainly from water or our food because of pesticide usage or something else? It's going to take time to parse that out and really understand the main mechanism that moves these chemicals into us. We know that plastics are one of them. There's no doubt about that.

ALS: How do you see testing fitting into this bigger picture of what we need to do?

Dr. Mason: It helps us to understand those mechanisms like determining the biggest contributor to microplastics in the environment. Is it coming from the manufacturing of clothing or is it all the litter that we see on the side of the road?

Testing helps us identify places where we can intercept that system and stop that leakage. So, if the problem is washing machines, it could mean putting filters on washing machines in addition to the dryers.

Finding means to reduce litter is one thing, but what if we stop it before it's even litter? What if we don't have plastic straws?

Monitoring helps us to understand the system as a whole and where we can intercede. It also helps us to understand where those microplastics hotspots are and why those hotspots are where they are.

It also helps us to understand how this stuff is moving. So, when someone in industry points to the ‘five rivers’ studies and says the problem is Asia – no, it's our trash that ended up in Asia. So, we have to understand how these things are moving as well.

Fibers are a good example of that. I don't think anybody was thinking of microplastic as being an air pollution problem. It was a water problem, but we started finding in our Lake Superior study all these microfibers, but Lake Superior is not densely populated.

Few people live around Lake Superior, and yet we're finding tens of thousands of microfibers in the water, and we're like, “Why”? And suddenly it hit us. Big lake, big contact with air. It's coming from atmospheric deposition, and we were thinking about that just as the first air studies were coming out.

And then we started thinking about the manufacturing of clothing, not just the washing of clothing, but where it's manufactured, what happens in the emissions from those factories, and then how those move across the globe.

And that gets us back to the point that, yes, there are hot spots, but none of us are immune. It doesn't matter if you're living on the top of Mount Everest, you're going to be breathing this stuff in.

So that also helps us to understand microplastics. The data at this point shows that we're breathing in as much as we're eating. We can't just control this as a water pollution problem. We have to also be looking at air.

ALS: What do you see right now as some of the most important areas of research or specific studies that we need to focus on?

Dr. Mason: It's the human health studies. That's what's going to create action. It’s understanding the impacts of micro- and nanoplastics on human health.

Another area that I find fascinating is from our bottled water study. We discovered microplastics are actually coming from the bottle itself. It led to the birth of this new area of research where people are monitoring takeout containers and various plastic items and finding out how they're constantly flaking.

I find that fascinating because we don't think of plastics like that. But plastics are like skin, and skin is perpetually releasing skin cells right into our environment. We don't think of plastics that way, but they are. So characterizing and understanding the fragmentation of plastics.is another interesting area that's adding to the study of microplastics and human health. It's understanding that that these things are shedding from the plastic items that we use. Just the fact that your cheese is wrapped in plastic means that it's going to contain plastic. When you pick up food in a plastic container, when you open that container, the food is going to contain microplastics.

ALS: It’s like the apples at the airport that are individually wrapped in plastic.

Dr. Mason: Yeah, and bananas. It’s ridiculous. I mean, they already have a skin!

ALS: It seems our biggest challenge right now is to change the mindset of people about plastics.

Dr. Mason:

Yes.

ALS:

Thanks so much, Sam, for answering our questions and sharing your insights.

Should you be testing for microplastics?

Microplastics legislation is still in its infancy. To address health concerns about microplastics, some governments have begun regulating their presence in drinking water, and we can expect more regulation on the horizon.

How do I conduct microplastics testing?

ALS can help can conduct microplastics testing for clients seeking to comply with current regulations or proactively conduct microplastics analysis in anticipation of coming legislation.

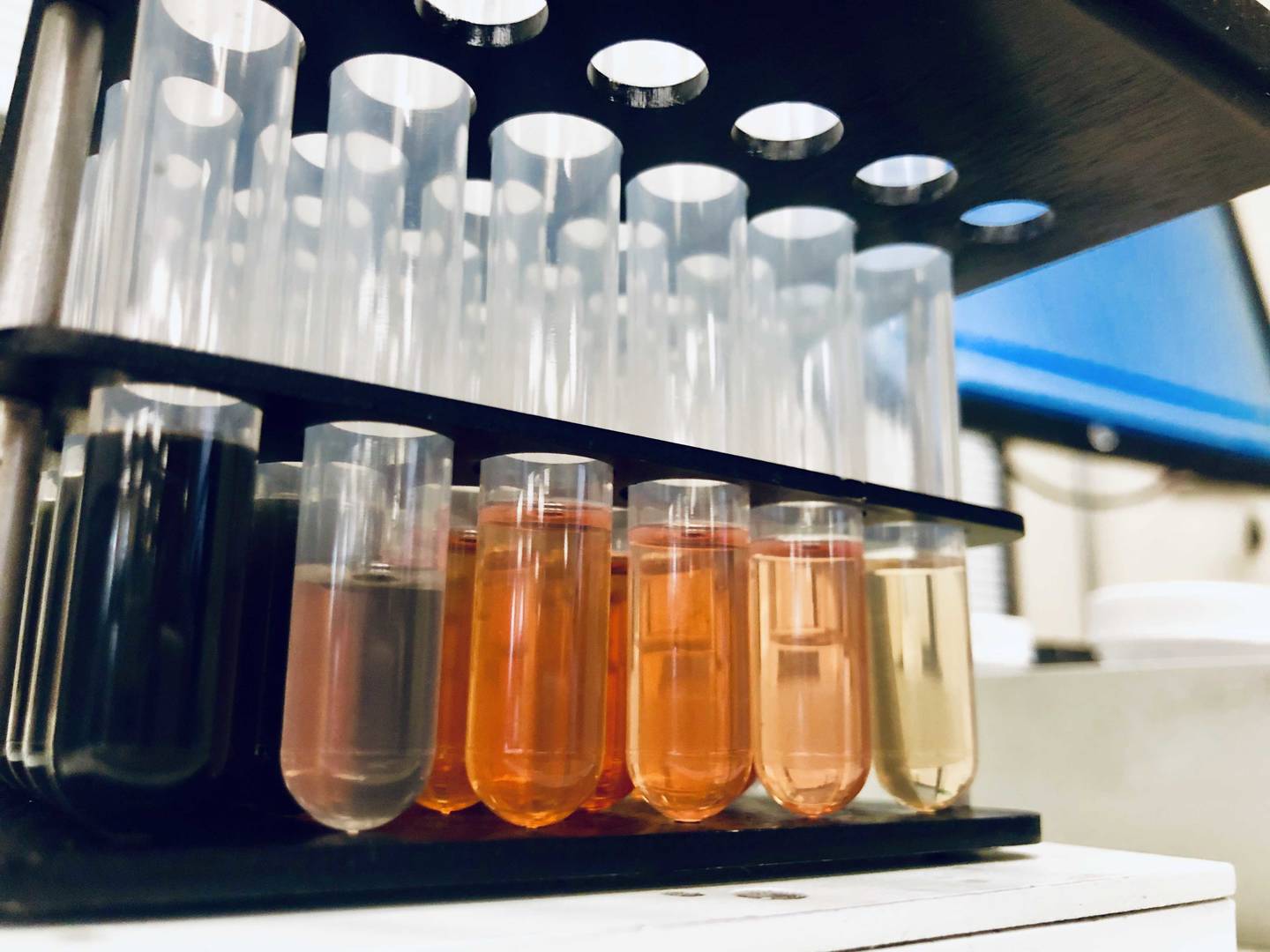

Nile red, FTIR and pyrolysis GC-MS are the most common methods of microplastics testing, all offered by ALS.

At the forefront of environmental testing, we have both the experience and instrumentation to test water, soil, sediment and biota for microplastics.

To find out more about microplastics testing, contact Morten Christensen at Morten.Christensen@alsglobal.com.

Learn more about Dr. Mason’s research at sherrimason.com

About ALS Limited

A global leader in testing, ALS provides comprehensive testing solutions to clients in a wide range of industries around the world. Using state-of-the-art technologies and innovative methodologies, our dedicated international teams deliver highest-quality testing services and personalized solutions supported by local expertise. We help our clients leverage the power of data-driven insights for a safer and healthier world.

References

https://www.nature.com/articles/s41591-024-02968-x

https://www.shannaswan.com/countdown

https://www.pnas.org/doi/10.1073/pnas.2300582121

https://www.spectroscopyonline.com/view/analyzing-nanoplastics-columbia-university-climate-school